16 EPILOGUE

© Ian Lawton 2020

[Please note that in the section on 'The Age of the Sphin' I refer to a paper written by my former co-author Chris Ogilvie-Herald. He has asked me to indicate that the 2019 version of this paper that I refer to below has now been updated, and for anyone interested in the details it can be found here.]

Since the original editions of this work were originally published there have been various developments worthy of mention. First, particularly in the first few years of the new millennium I engaged in a number of discussions with fellow researchers such as Robert Bauval, Chris Dunn and many others regarding the various theories surrounding the Giza Pyramids and Plateau and the Sphinx, based on what we’d presented in the original chapters. Details of these discussions, which took the form of email exchanges combined with publication of new papers, can be found on my website, but are now summarised here too.[1] Second, a number of further explorations have been attempted in the last two decades. We will tackle all of these in the order in which they’re originally mentioned in the main chapters.

THE TRUE FOUNDERS OF EGYPTOLOGY

We saw in chapter 1 that Jean-Francois Champollion is normally hailed as the ‘Founder of Egyptology’ because he was the first to decipher the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone. But in fact recent research by Dr Okasha El Daly, of the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology at University College, London, has shown that several Arabic scholars managed to accurately interpret certain Egyptian hieroglyphs nearly a thousand years earlier in the 9th and 10th centuries. In his 2008 book The Missing Millennium: Ancient Egypt in Medieval Arabic Writings he reports that foremost among them was Abu Bakr Ahmad Ibn Wahshiya, an alchemist who wrote about poisons, magic and the decipherment of ancient languages. What is more it seems there’s much, much more to be discovered in medieval Arabic manuscripts concerning their fascination with the knowledge possessed by the Ancient Egyptians.[2]

THE AGE AND PURPOSE OF THE PYRAMID

In the last two decades there have been a number of new or at least amended contributions to the debate surrounding the age of the Pyramid that I originally discussed in chapter 2. Perhaps the most surprising is that Robert Bauval has joined with those who believe that the Great Pyramid contains encoded mathematical and geometric knowledge. In his 2018 book Cosmic Womb: The Seeding of Planet Earth – which is somewhat incongruously co-authored with astrobiologist and panspermia exponent Chandra Wickramasinghe – Bauval concentrates on an apparent personal obsession with numerology, and on the advanced mathematics he believes to be encoded in the Great Pyramid. Of course we’ve been here before with the Pyramidiots, but at least we’re not dealing with biblical prophecy this time. More than this, though, having previously argued that the Giza Plateau was only laid out to reflect the night sky c. 10,500 BCE, he has now either changed his mind or completely come out of the closet – one can never be sure which – by arguing that such complexity could only have been achieved by extraterrestrial visitors who must have constructed the Pyramid at that magical earlier date, or at least provided important input. This means he’s now not only a fully paid up member of the redating school, but has also joined the likes of Zecharia Sitchin as an Ancient Astronautist.

While we’re discussing this date, it’s interesting to note what sceptical researcher Jason Colavito has to say about its origins:[3]

The Victorians used ‘10,000 BC’ as a marking point for the end of the Ice Age, and Bible-thumpers of the Old Earth persuasion suggested it as the date of the Flood. [Karl Josias von] Bunsen, the most widely cited writer on Egypt in that era, gave 10,000 BCE as the time when Egyptian religion was founded, under Osiris, after the Flood… using the numbers given in Manetho’s King List.

Meanwhile Scott Creighton’s 2017 book The Great Pyramid Hoax picks up on Sitchin’s claims about Richard Howard Vyse faking the infamous Khufu quarry marks – arguments I thoroughly analysed and dismissed in chapter 2 – and takes them to a whole new level. In particular he attempts to quote from Vyse’s hand-written journal, although the latter’s handwriting is extremely difficult to read, indeed virtually impossible in places. Martin Stower has again offered a thorough rebuttal of Creighton’s interpretation of the key passage and, while this is too intricate a discussion to reproduce here, it too can be readily accessed on Colavito’s website.[4] Above all, even if Creighton’s arguments about the quarry marks held water – which they don’t – he completely ignores all the contextual and other arguments against the Pyramid being older than Khufu’s reign. Just like our next researcher in fact…

Turning to the purpose of the Pyramid, on my website I’ve engaged in a spirited discussion with Chris Dunn about his 'Giza Power Plant' theory, which I covered briefly in chapter 3.[5] Again it’s way too detailed to reproduce in full here. Suffice to say, though, that I believe it’s not unfair to suggest he seems to have little defence against my argument that it completely ignores the religious context of pyramids in general, of their surrounding complexes, and of the texts found inscribed on the walls of their chambers from the 5th Dynasty onwards.

PYRAMID AND TEMPLE CONSTRUCTION

Generally, plenty of support for the orthodox view of pyramid and temple construction that I expounded in chapter 4 has been forthcoming in the last two decades – notably from independent researchers like ourselves with no axe to grind. For example, in 2003 architectural designer Seamus Chapman published Building Egyptian Pyramids: Achieving the Impossible, in which he covers all aspects of construction, including a detailed and original proposal for a ‘platform and ramp’ system. Then in 2018 Craig B Smith, the former president of a global engineering firm, gave us How The Great Pyramid Was Built, which looks at all aspects of the construction effort, including the incredibly sophisticated project management that was required. As a former project manager myself this is something I’ve always been in awe of.

MEGALITHS

Previously I concluded that I couldn’t provide a logical explanation as to how the 200-tonne megaliths were raised up into the walls of various of the temples. Colin Reader, a British geological engineer whose contribution to the debate about the age of the Sphinx will be considered shortly, has provided important input here. In a paper specially prepared for my website he demonstrates, using detailed calculations of thrust and stability, that a sand ramp would be able to support such huge blocks during construction.[6] Moreover another correspondent, George Forrest, suggests that the logic behind using such huge blocks was their stability in the earthquake conditions that we know affected the Plateau in the past.[7] So perhaps this is another enigma that has now been solved.

TRANSPORTING AND LIFTING STONE BLOCKS

Forrest also admonishes my lack of understanding of the mechanics of friction when discussing the number of men required to drag the huge megaliths. In chapter 4 I suggested it would take 210 men to drag a 70-tonne block on the flat, assuming each man could exert a force of a third of a tonne. But Forrest says that if the coefficient of friction is only, for example, 10 per cent, then that figure is reduced to only 21 men. He does however agree that a 1:10 slope – the figure I used for all my calculations in chapter 4 – requires an extra 10 per cent or 7 tonnes of force, therefore an extra 21 men. Overall, then, the numbers can perhaps be significantly reduced from my original estimates.

Forrest emphasises that the key to all this is reducing the coefficient of friction. Sledges massively increase this by reducing contact area, so would only have been used for carved objects that needed to remain entirely undamaged – although I’d argue that wooden sledges don’t have to have runners, they could be flat-bottomed. In any case he goes on to suggest that the main construction blocks would have been simply dragged along flat surfaces to the construction site wherever possible, the key being the lubricants used. In this context he reports that Nile mud is particularly slimy, while tubular roots – for example, potatoes – also make an excellent lubricant. Apparently the latter were used to transport the Easter Island statues, and recent experiments have confirmed that they’re a very efficient lubricant. Their particular importance here would be that, perhaps when mixed with mud, their fibrous nature would prevent the whole concoction from being squeezed out at the sides.

Perhaps most interesting of all, though, Forrest briefly picks up on the issue of Masoudi’s report that the blocks moved when struck, as quoted in chapter 4: ‘It is likely that the very large stones were cut to a length that enabled them to resonate. A sharp tap on the side would result in a “magical” loss of weight. This of course could be the source of the levitation stories.’ Did the Ancient Egyptians find a way to lower the friction still further by this method?

One researcher who picks up on this, among other things, is Mike Molyneaux, a New Zealand-based oil and gas engineer.[8] As suggested by the title of his 2006 paper Real Life Experiments that Reveal the Ancient Art and Techniques of Building Egyptian Pyramids, rather than just using conjecture he has conducted real-life scale experiments to check various theories. One aspect he emphasises is that, when attempting to perform the final positioning of megalithic blocks, wooden battering rams can generate ‘sufficient acoustic and mechanical energy’ to accurately inch them into place.

He then switches his attention to the more general hauling of blocks up inclined slopes. After using small-scale models, he engaged a real-life girl weighing 31 kg to attempt to haul a loaded slab up a concrete 1:10 slope: ‘She could haul almost six times her own weight [170 kg] if the weights were supported on rollers, but only a little over her own weight when rollers weren’t used.’ By contrast: ‘She could haul nearly twice her own weight up a 1:10 wooden track covered with oil, water and sand.’

He then switched to experimenting with a counter-weight system, with the girl hanging on the end of a rope pivoting over a steel pole, with the slab resting on rollers running over a lubricated wooden track – and again the idea of a sharp shock to the stone comes into play:

Her own weight could not initially shift the 170 kg load mounted on rollers. Friction between the rope and steel pole was considerable. However a sharp knock with a pole sent the loaded slab moving up the smooth wooden board on the 1:10 slope. It was also quite obvious that, once in motion, the loaded slab accelerated to about twice the speed at which she could haul the load along on foot… In conclusion it appears that the use of wet clay or wet, oiled timber facilitates the transportation of smaller stones on wooden sledges along tracks and ramps for the construction of the more primitive, smaller pyramids. For later pyramid designs using much larger stones the wooden plank and roller system would have been essential, especially near the top of the pyramid where working space for large teams of labourers is very limiting, making some manoeuvres impossible.

In terms of numbers, Molyneaux adds: ‘A team of 20 men would be required to haul 11-tonne stones up a 1:20 ramp. To start the stone moving they would need the assistance of an impact with a suitable ram swung by 20 men from the team working at the bottom of the ramp.' He continues that apart from speed of movement and the need to work in limited space as one nears the apex, the counterweight system has other advantages. First, the haulers use an entirely different staircase, so aren’t slipping on any lubricant. Second, they use only their arms one way and only their legs the other, so can work for longer without fatigue. By contrast he argues the spiral ramp technique I championed in chapter 4 is flawed in that towards the top one can’t run ropes around a corner that doesn’t yet exist – while constructing sufficiently robust temporary corners would just be a waste of effort, something these expert architects and builders would be keen to avoid. Remember too that we’re not just talking about small stones at this point, because the casing stones still weigh an average of around 11 tonnes.

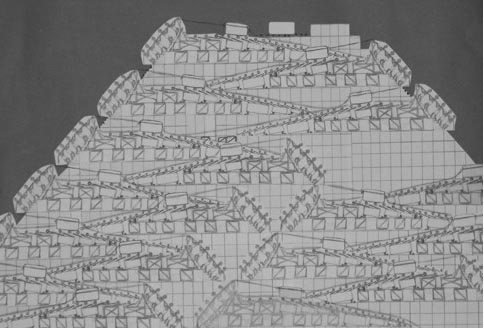

Figure 38: Zigzag Ramps and Staircases using the Counterweight System [9]

Overall, then, for the Great Pyramid Molyneaux proposes a) a single primary ramp on one side for the lowest levels; b) on the other sides and the rest of that side, a counterweight system as per Figure 38, consisting of smaller zigzag ramps constructed on ledges, using stone that would later be reused in the edifice itself, accompanied by wooden staircases for the haulers; and c) internal ramps where appropriate.

Interestingly a French architect with a lifelong passion for Ancient Egypt, who has studied the Giza monuments for over twenty years, has come to some very similar conclusions.[10] In the early years of the new millennium Jean-Pierre Houdin, in combination with his retired civil engineer father Henri, proposed a combination of a) a relatively small, straight external ramp, rising to only one third height, whose materials would be reused in the construction of the higher levels; b) an internal spiral ramp; c) wooden lifting machines at the very top; d) two temporary internal pyramids to erect the Queens and then Kings/Relieving Chambers and their roofs; and e) counterweights running on wooden frames in the Ascending Passage and then Grand Gallery to lift the largest blocks. Although Molyneaux assures me that there are in fact significant differences between his and Houdin’s approaches, from a layman’s point of view they both appear to provide a ‘horses for courses’ approach that uses the most efficient solution to each different problem.

Houdin continued to refine his theories, publishing a paper in Archaeology magazine in 2007 along with American Egyptologist Bob Brier, which was expanded into the book The Secret of the Great Pyramid the following year. His work assumed that each ramp ended in an open space on each corner, and in 2008 Brier and a National Geographic film crew explored a notch in the north-east edge of the edifice, and an L-shaped room behind it, that seemed to provide evidential support.[11] Then in 2010 Houdin teamed up with researchers from the Université Laval in Québec, who apparently used infrared thermography to verify the presence of his internal ramp. He also collaborated with a French company called Dassault Systems and with the Boston Museum of Fine Arts to produce a fascinating documentary containing 3D-modelling of how the Pyramid was constructed.[12]

GEOPOLYMER THEORY

After the original editions came out I appeared on a US radio show, as a result of which I was contacted by Margaret Morris, an avid supporter of Joseph Davidovits’ geopolymer or cast-block theory that I more or less dismissed in chapter 4. In a flurry of correspondence she rightly took me to task on at least one issue, so much so that I presented a new positioning statement on my website.[13] The particular original objection on which she concentrated was my contention that both the core and casing blocks in the Great Pyramid are extremely non-uniform in size, meaning standard moulds couldn’t have been used. But Morris claims that the blocks may have been formed in situ using planks and boards, which would lead to a non-uniform size. For his part, on the FAQ section of his website Davidovits seems to differ somewhat on this, maintaining that all pyramids deliberately used a combination of something like five different sizes of block because ‘this heterogeneity gives the monuments the ability to resist earthquakes by avoiding the amplification of seismic waves’.[14] Either way, these seem sensible counter-arguments.

Nevertheless my other objections remain. First, Davidovits himself accepts that the larger and heavier granite blocks almost certainly weren’t cast. His reaction is: ‘They represent less than 0.1% of the total blocks. Workers had 10 years to install them in the pyramid… In short, we don’t care! We care about the 99.9% of limestone blocks.’ While this might be half reasonable, we still need to understand how these larger, heavier blocks were raised and placed in situ without the requirement for huge ramps, and most obviously using only counterweight systems. I am not claiming this is necessarily impossible, but it does need further elaboration for an all-encompassing theory to work. Second, neither Davidovits nor Morris seems to be able to properly tackle the existence of quarry marks. They are rough-painted because never expected to be seen, they often lie sideways or upside down – even underneath surveying and levelling lines in places – and they often mention ‘crews’ of Khufu's workmen; some even say ‘this way up’. If they were only on granite blocks it might be possible to explain them away, but in fact they’re exclusively found on limestone blocks that are supposed to have been manufactured.

It is interesting to note that on his website, after each objection to his theory has been countered, Davidovits continually repeats the mantra his ‘supporters’ should use: ‘Believing in the artificial stone theory, or countering it, is simply no longer relevant. It has become a fact, a truth.’ It is a personal view, but this almost smacks of desperation and of a political-style campaigning message, which doesn’t necessarily inspire me at least to fall into line. However both he and Morris have now released additional books on the subject; and it’s certainly not an idea I’m prepared to reject out-of-hand until other, more definitive evidence one way or the other is forthcoming. We might also note that Davidovits now claims that all the early Egyptian pyramids were built using cast stone, as well as some other early structures around the world – such as, for example, Tiahuanaco and Pumapunku.[15]

ADVANCED MACHINING

I have also had discussions on my website with Chris Dunn concerning his ‘advanced machining’ hypothesis, to follow on from the conclusions I drew in chapter 4.[16] Having read my report of John Reid and Harry Brownlee’s inspection of Drill Core No. 7, which suggested that it didn’t exhibit spiral striations, Dunn flew to London to inspect the core for himself. His report came up with two important new findings.[17] First, although on initial inspection he thought that Reid and Brownlee must be right, he still decided to check for spirals by wrapping a length of thread around the apparently random and unconnected striations. He found that the groove varied in depth as it circled the core, and at some points there was just a faint scratch, difficult to see with the naked eye. Nevertheless, he suggests that he did find spiral striations – although not a single spiral with a pitch of .100 of an inch as described by Petrie, but two intertwined spirals of similar pitch.

I had already suggested that, even if spiral striations were found, they could easily be the result of the drill bit being withdrawn from the workpiece, thus telling us nothing about the feed rate of the drill. Prior to his report, Dunn had also accepted this possibility. However, during his visit he measured the depth of the grooves at up to .005 of an inch, and now suggests that there would be insufficient lateral force to create such deep grooves when the bit was merely being withdrawn. At the time of writing I’ve been unable to substantiate whether or not these new elements of Dunn’s analysis are sound. However, he’d previously maintained that the primary factor that made him consider ultrasound was the fact that the quartz was cut deeper than the surrounding feldspar – yet in correspondence it’s clear he accepts Brownlee’s suggestion that this may have been caused by ripping. Since his report adds nothing definitive on this subject, it remains unclear exactly what conclusions he draws from his new analysis – and indeed whether or not he believes it supports his suggestion that ultrasound was employed.

Meanwhile my attention has been drawn to three other important sources that reinforce the case for conventional drilling methods being employed by the Ancient Egyptians. The first is a book originally published in 1930 by Somers Clarke and Reginald Englebach entitled Ancient Egyptian Construction and Architecture. Among many other highly enlightening descriptions and illustrations, this contains an Egyptian depiction of a weighted drill borer being used (see Figure 39), and mentions evidence of tubular bits. The second is a series of excellent papers prepared in 2002 by Archae Solenhofen. In particular Ancient Egyptian Stone Vessel Making and Ancient Egyptian Copper Coring Drills contain numerous illustrations, drawings and photographs of stone vessels, and the methods used to hollow them out using weighted tubular drills – sometimes followed by a stone borer of larger diameter, to hollow out the interior.[18] The third is a series of equally enlightening experiments performed by Denys Stocks of Manchester University, which commenced in the mid-1980s, in which he used wet sand as a grinding slurry and produced granite drill cores with striations that appear remarkably similar to those on No. 7. This and many other experiments are recorded in his 2010 book Experiments in Egyptian Archaeology.

Figure 39: Egyptian Illustration of a Weighted Drill Borer [19]

Above all, the practical experimentation performed by researchers such as Stocks, Reid and Brownlee is more likely to resolve these issues than any amount of theoretical speculation.

ACOUSTIC RESEARCH

In chapter 4 I also discussed how Tom Danley, Chris Dunn and John Reid all feel that the King’s Chamber and its sarcophagus have resonant properties. Reid in particular suggested that these were tied in to rituals that might have been conducted therein, and in the early years of the new millennium backed this up by performing cymatics experiments whereby he stretched a membrane across the top of the coffer and sprinkled it with sand, then played certain musical notes to see if patterns formed.[20] Most intriguing is that some of the resulting images bore a close resemblance to Egyptian symbols such as the 'Eye of Horus' and the 'Djed' pillar.

THE HUNT FOR SECRET CHAMBERS

Picking up from where we left off in chapter 6, the last two decades have seen the emergence of at least one new theory about secret chambers in the Pyramid, along with concerted and ongoing attempts to locate same.

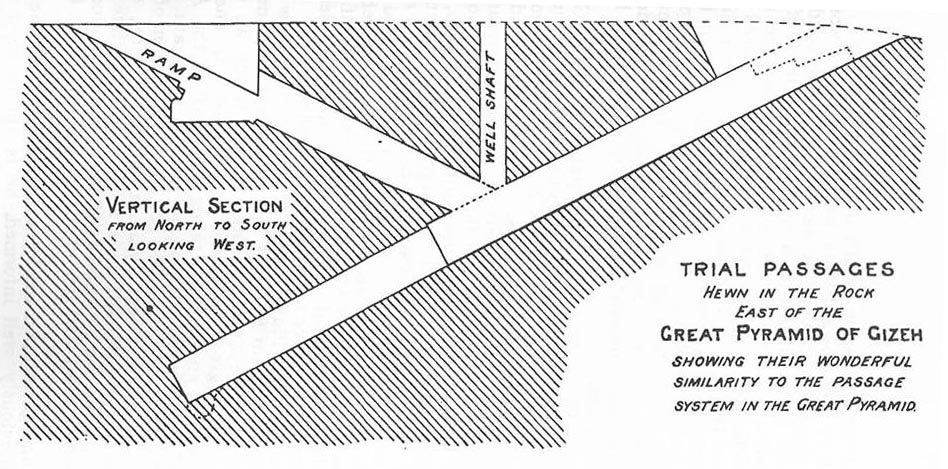

THE TRIAL PASSAGES

In the late nineteenth century William Flinders Petrie was the first to draw attention to the so-called ‘trial passages’ that lie about 300 feet to the east of the Great Pyramid, just north of its original causeway. Subsequently the Edgar brothers also explored them thoroughly.[21] All commentators seem to agree that they represent a scale replica of the Descending and Ascending Passages – shortened in length, but with the same heights and widths – even down to replicating the base of the Grand Gallery, the beginning of the Queen’s Chamber Passage, and the slight narrowing of the Ascending Passage at its base. The only difference is that in the trial system a vertical shaft rises up from the intersection of the Descending and Ascending Passages (see Figure 40). Most people assume this is supposed to represent the Well Shaft, although in the real thing this starts much lower down the Descending Passage and finishes at the top of the Ascending Passage (see Figure 2).

Figure 40: The Edgars’ Drawing of the ‘Trial Passages’

But in 2001 British researcher Mark Foster pointed out that it would hardly serve any purpose to dig trial passages out of bedrock as a learning exercise for real ones that would be largely man-made because located in the superstructure; also that no equivalent has been found for any other pyramid.[22] His alternative explanation was sparked by Ralph Ellis’ theory that Mamun dug his tunnel from the inside out, rather than vice-versa as normally assumed.[23] Ellis maintains that, first, ancient sources suggest the original entrance to the Descending Passage was well-known and open long before Mamun’s time. Second, his tunnel manages to intersect with the junction of the Descending and Ascending Passages, despite this being some 24 feet to the west of the north-south centreline. Remember the traditional view, described in chapter 1, is that his team heard the lintel sealing off the Ascending Passage fall down and so changed direction. Yet as Foster points out there’s no real turn to the left at the end of Mamun’s tunnel. So is this really how he located the Ascending Passage?

This is where Foster maintains that the ‘trial’ passages were no such thing, but deliberately designed to provide a clue as to how to find the Ascending Passage. He backs this up by suggesting that a pair of lines has been scored on the walls of the ‘trial’ Descending Passage that correspond to a similar pair of lines in the real thing, which when used as scaled distance-markers provided the ‘key’ for where to find the real Ascending Passage. What is more, he says, Mamun unlocked this key. Why then did he dig a horizontal passage out again? Foster and Ellis together maintain that Mamun found the King’s Chamber empty apart from a sealed sarcophagus, at which point he insisted that the lid be removed. They add that, furious and frustrated when it was revealed to be empty, Mamun knew the coffer itself was too large to be removed through the entrance to the chamber – but its lid, if angled diagonally, could be. Unfortunately though it couldn’t be angled around the junction of the Ascending and Descending Passages, forcing a desperate Mamun to insist on the digging of an entirely new tunnel to remove it – to prove that at least something had come of all his efforts.

No one can say exactly what Mamun found and subsequently did, but all this sounds pretty reasonable to me. Somewhat more speculatively, Foster concludes that the vertical ‘trial’ passage represents a clue to an as-yet undiscovered equivalent in the real thing, which may well lead to one or more unknown chambers. He adds that there are several other pieces of evidence pointing towards this. First, the existence of the 'girdle stones' that provide reinforcement in the Ascending Passage, suggesting some sort of chamber might lie above them. Second, a number of references in Gantenbrink's full report where he mentions anomalies in the southern air shafts.[24] These include floor damage, cut marks for precision joints, and one unique vertical joint – all, says Gantenbrink, indicative of possible hidden chambers or structures above or below the shafts.

Of course these latter would be well away from Foster’s proposed undiscovered passage on the north side of the Pyramid, and generally this extra element of his argument may or may not be wide of the mark. But even if it were it wouldn’t invalidate the remaining excellent suggestions from himself and Ellis. No one has as yet attempted to uncover his proposed vertical passage – but the next set of explorations might provide an answer as to where, if it does exist, it might lead…

THE SCANPYRAMIDS PROJECT

Fast forward to 2015 and the launch of the ‘ScanPyramids Project’, an International mission of Egyptian, French and Japanese scientists led by Cairo University and the French Heritage Innovation Preservation (HIP) Institute. They would use non-invasive technology such as muon radiography in an attempt to locate any unknown internal structures or voids in the Pyramid. This is a little like taking an X-ray, but of a building, and in chapter 6 we saw that Luis Alvarez used similar techniques in Khafre’s Pyramid during the 1960s. Although he failed to find anything of significance he only scanned 20 per cent or so of the building and, in any case, detection equipment has significantly improved since then.

Figure 41: Voids Revealed by the ScanPyramids Project [25]

The team’s first discovery came in 2016, when some sort of space stretching back at least 15 feet – possibly a corridor – was detected behind the chevrons on the north face of the Great Pyramid. A little way underneath these is the original entrance to the Descending Passage, now covered by a grill because visitors are instead directed to use Mamun’s horizontal tunnel. But this new space or corridor, labelled ‘ScanPyramids North Face Corridor’ or SP-NFC (see Figure 41), lies higher up behind them, and could represent an entirely different way into the structure – perhaps, for example, a horizontal passage linking up with the base of the Grand Gallery.

Arguably even more exciting was their discovery the following year of a previously unknown and sizeable void some 50 feet above the Grand Gallery, which they called ‘ScanPyramids Big Void’ or SP-BV (see Figure 41).[26] After further tests in 2018 and 2019 in the Grand Gallery, King’s Chamber and Relieving Chambers, its estimated length was increased from 100 to around 130 feet, with a height of something like 30 feet. Mark Lehner and Zahi Hawass seemed pretty sceptical about it at the time, arguing that the structure is like Swiss cheese in places. What is more there remains some debate about whether it lies in a horizontal plane or slopes as shown in Figure 41, which could have a significant bearing on its purpose. But Brier has suggested it could have been used as part of a similar counterweight system to the one proposed by himself and Houdin for the Grand Gallery, this time for higher courses.[27] In any case, at some point the ScanPyramids team are hoping to conduct further scans in the Relieving Chambers, which obviously lie closer to SP-BV.

In the meantime the question remains at to how far in SP-NFC extends, and whether it appears to join up with other corridors or even with SP-BV itself. The ScanPyramids team themselves are hoping to refine their understanding of its exact location, but in the meantime they’ve enlisted the services of a French team from the National Institute for Computer Science and Applied Mathematics, led by Jean-Baptiste Mouret and supported by Dassault systems – who we saw working with Houdin above.[28] They have been designing a miniature ‘scout robot’ armed with multiple lights and a high-definition, multi-directional camera that will be able to pass through a small hole only 1.5 inches in diameter, which will be drilled through the appropriate blocks, to explore what’s on the other side. If this reveals anything promising a second ‘exploration robot’ will enter, which will take the form of a flying blimp armed with cameras and so on that will only be inflated once through the hole. While final technical trials continue, at the time of writing this work is currently awaiting the final approval of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities.

This delay may have something to do with a Japanese team from Kyushu University being asked to confirm the ScanPyramids team’s findings, particularly in relation to SP-BV.[29] They plan to use a ‘newly developed’ muon detector that will be placed inside the Queen’s Chamber for a month, with their findings due to be released later this year.

THE AGE OF THE SPHINX

Since the original editions came out considerable material has also been published on my website concerning the age of the Sphinx.[30] Not least of this is an important contribution by the aforementioned Reader, who entered the fray in 1997, although we only became aware of his work after the first edition of this book came out. Initially we were highly impressed by his analysis and proposal for an earlier date for the monument, although not significantly earlier at only c. 4500 BCE. This led to me publishing his paper Khufu Knew the Sphinx on my website, while we included a synopsis in the Epilogue to the second edition. However this has now been removed, albeit that his original paper can still be found on my website. Why? Because it is potentially superseded by more recent research conducted by my former co-author Chris Ogilvie-Herald.[31]

MODERN FLOODING

He has unearthed a number of eye-witness accounts that reinforce those we presented in chapter 7 from James Harrell, Kent Weekes, Alexander Moret, Richard Howard Vyse and John Greaves regarding sudden storms and flash-flooding on the Plateau in recent times. He quotes a number of reports of massive flooding in the Cairo area in the modern era, as well as more specific reports of serious flooding on the Plateau from the Victorian era and on into the twentieth century.

OLD KINGDOM FLOODING

Perhaps more interesting and relevant is Chris’s evidence for flooding in Giza and the surrounding area back in the Old Kingdom itself. First he discusses the administrative area to the south of the Plateau that housed the various workers who built the Giza monuments, known today as Heit-el-Ghurab or ‘the Lost City of the Pyramid Builders’. He reports that ‘excavations have shown the town was repeatedly destroyed by flash flooding and rebuilt during the reigns of Khafre and Menkaure’. As these floods became progressively worse Menkaure had a defensive barrier built, known today as the ‘Wall of the Crow’, but even this wasn’t enough and the workers town apparently flooded 10 times within about 45 years. He adds that George Reisner, who we met in chapter 1, found evidence of flash-flood damage to the walls of Menkaure’s Valley Temple ‘that could only have occurred at some point between the 4th and 6th Dynasties’, and joins others in asking if this Is why there are only three pyramids at Giza, even though it’s such a prime site?

Chris then moves on to the 4th Dynasty mastaba tomb of Kaunisut, which lies only a few yards to the south of the Sphinx enclosure. Using a number of photographs for reference he reports that the contemporary ditch leading to it ‘exhibits fissuring and coving due to flooding and runoff,’ and adds: ‘Although on a smaller scale the similarity to the Sphinx enclosure walls is undeniable.’

He also cites a number of teams who have worked at the Saqqara Necropolis, some 15 miles south of Giza. They universally report serious contemporary flood damage to tombs and other structures dating to the 6th Dynasty. Apparently many efforts had been made to rebuild these structures, and to counter the flooding in later tombs with revetments and drainage pits. But, having been a popular site for non-royal burials during the 5th and 6th Dynasties, it was subsequently abandoned – almost certainly because of the flooding problem. He adds that there are similar reports from Abusir, and concludes that all this as evidence of ‘an intense rainy period that lasted for hundreds of years’ during the latter part of the Old Kingdom.

To complete this section Chris discusses the fact that Houdin, whose construction theories we discussed above, has developed a hydrological model of the Giza Plateau as it would have been during the 4th Dynasty. This emphasises how the building of the pyramids would have completely changed the way rainwater behaved, and in ways the architects may not have fully foreseen. When the smooth casing blocks were still in place on the three pyramids the run-off would have been amplified compared to today, cascading in torrents down the gradient of the Plateau – which in any case slopes downhill from the north-west towards the south-east, exactly in the direction of the Sphinx enclosure. Houdin’s model also shows how the Khafre causeway would have acted as a dam to force even more run-off along the length of the south enclosure wall and into the enclosure.

THE OLD QUARRY

Chris also raises Reader’s objection that an old quarry that lies between the pyramids and the Sphinx would act as a sink for any rainstorm run-off, even though it’s been backfilled with rubble. He quotes Karl Lepsius, who we met in chapter 1, who witnessed a huge storm at Giza and saw the massive torrents collecting in ‘a deep hollow behind the Sphinx’. However it’s not entirely clear what this really implies and which side of the debate it supports.

BURIED OR NOT?

All this newly collated evidence is surely important. But there is one other factor that underlies the whole argument – which is that all the above-mentioned flash-flooding and rainwater run-off can only have had an impact on the Sphinx enclosure if it wasn’t filled in with sand. In chapter 7 we saw that the consensus view is that it’s been buried up to its neck for approximately two-thirds of its orthodox 4500-year existence. But, for example, how long did the enclosure remain clear after the monument was built? We have no idea. If it was only for a few hundred years or even less, would this have been long enough to cause significant erosion? We also saw that, based on the evidence of the Dream Stele between its paws, Thutmose IV’s supposed clearance of the enclosure c. 1400 BCE is thought to represent the first time this had taken place since it first became buried. Yet, as we observed in the original Epilogue, there’s little within the text of the stele to justify this assumption because the relevant line simply states: ‘The sands of the Sanctuary, upon which I am, have reached me.’ This is by no means a clear indication of the volume of sand within the enclosure at the time, and one could equally argue there was only a relatively small build up around the base.

While much of the argument for the Sphinx being buried for significant periods relies on ‘no reports of restoration or worship’ – as per Figure 27 – Chris adds that ‘absence of evidence doesn’t equate to evidence of absence’. But, unless further careful study of other New Kingdom iconography and texts were to reveal that the enclosure was free of sand for substantially longer than is normally assumed, it’s extremely difficult to draw definitive conclusions about all this. This is especially true when other forms of weathering as discussed in chapter 7 – chemical, capillary, atmospheric and so on – have come into play.

SOMETHING OF A SCHOCH?

We noted earlier that Robert Bauval has in recent years come out fully as an Ancient Astronautist and redater. But in 2017, the year before he gave us The Cosmic Womb, he teamed up with Robert Schoch to write Origins of the Sphinx. With each author contributing distinct chapters this is mainly a rehash of all the arguments presented in both their earlier works. But there is one interesting new development. Rather than the more conservative dates he preferred in the past, Schoch tells us that he too now accepts a dating for the monument of c. 10,000 BCE.[32] Chris thinks this may well have had something to do with his upbringing, in particular by a grandmother who Schoch has admitted was a committed theosophist.[33]

CONCLUSION

On balance, and partly aided by Chris’s new research, I’m inclined to stick with our original conclusion: that, on the balance of probabilities, and given the whole context of the Plateau, the orthodox date for the Sphinx is most likely the correct one. Perhaps even more important I’d argue that any suggestion that a significantly earlier date such as 10,500 BCE is required to explain the weathering is likely to be extremely wide of the mark.

THE ENIGMA OF THE SHAFTS

This is the area where there have been perhaps the most important and intriguing updates to the material originally discussed in chapter 8.

THE METAL RODS

It has been brought to my attention that the metal rod that still resides in the northern Queen’s Chamber shaft may not have belonged to the Dixon brothers at all. In several chapters I briefly mentioned the Scottish brothers John and Morton Edgar in the context of their being proponents of the theory that the Great Pyramid’s detailed measurements are a symbolic reconstruction of a biblical timeline – and certainly the bulk of the three-volume Great Pyramid Passages and Chambers, published between 1912 and 1924, is all about this topic. But I wasn’t previously aware – although perhaps might have guessed given the context – that their work also contains a huge quantity of excellent drawings and plates, as well as massively detailed reports of the features and measurements of the Great Pyramid and others.

More specifically in the first volume they describe how they first visited the Pyramid in 1909 and found the southern King’s Chamber shaft quite clear and open to the air, while its northern counterpart was seriously blocked with debris that had accumulated from the outside.[34] John passed on in 1910, leaving Morton to write the second and third volumes on his own, but it’s not commonly reported that on a return visit in 1928 the latter gained permission from the authorities to clear these shafts, which by then were both clogged up.[35] He employed local workmen to use a ‘long boring rod’ with a ‘metal scoop’ on the end, then on completion of this arduous task – remember the shafts are several hundred feet long – got them to construct brickwork around the exit points to prevent further ingress of debris. But his investigations into the Queen’s Chamber shafts – the first since the Dixons’ endeavours more than half a century earlier – were even more revealing and worth quoting in full:

I ordered several long steel rods from an engineering firm in Cairo. The length of these rods varied from thirteen to sixteen feet, and I had them threaded at each end and had screw-couplers made so that the rods might be coupled together in one continuous length. At the end of one of these rods I had a ball of wood fastened. This was to prevent the end of the rod sticking in any joint or rough pieces of masonry. The ball glided over all inequalities. I began by probing the North Air-Channel of the Queen's Chamber, pushing in the rod with the wooden ball at the end of it first, and then coupling another rod to it and pushing that inward, then a third rod coupled to the other two – and so on, one rod after another. I found that all the rods that I had provided myself with in the first instance, passed up the channel without hindrance, and I had, therefore, to get a further supply of rods. These rods were of flexible steel, because the channel on the north side of the Queen's Chamber does not proceed directly upward in a straight line, but curves around toward the west to avoid the intervening masonry of the Grand Gallery. The rods, therefore, had to bend around this curved part. The North Air-Channel of the King’s Chamber is also bent around the intervening masonry of the Gallery on the west side.

I managed to push the rods up the Queen's Chamber North Channel to a distance of 175 feet, and then, unfortunately, the rods broke. The strain of passing around the westward bend proved too much for them. About a week later with some fresh rods I made another attempt to probe the length of this North Channel, but again my rods broke after I had pushed them upward for 175 feet. I was a little more successful in probing the length of the South Channel, for beyond the bend at the lower end this channel is straight… I managed to push the rods up the South Air Channel to a distance of 208 feet, and then they struck against some obstruction beyond which I could not go. About a week later I again probed this South Channel and could not get beyond 208 feet. So far as I can judge this is about twenty feet short of the outside of the Pyramid on the south side. I made a search for the outer end of this South Channel, spending several days on the south flank of the building, but could not detect any opening. Probably some future investigation may prove more successful.

So it appears that Morton Edgar was the first person to provide any sort of measurements of the length of the Queen’s Chamber shafts. For the southern one Gantenbrink recorded that Upuaut travelled 213 feet before reaching the ‘door’, and estimated that there were another 50 feet to go before reaching the outside of the edifice. The first number corresponds well with Edgar’s, even if the second varies somewhat – possibly because the latter could only make a rough guess at the angle of the shaft based on that of its northern counterpart, whereas Gantenbrink was working from accurate measurements. Meanwhile Edgar gave a reading for the northern shaft of 175 feet before an obstruction was encountered. While Gantenbrink provided no equivalent figure because Upuaut couldn’t negotiate the first kink, this seems somewhat short of what we now know lies at the end…

THE LATERAL DEVIATION OF THE NORTHERN SHAFTS

I originally came to the conclusion that I couldn’t properly explain the lateral deviation in the two northern shafts, other than certain potential alignments both between them and with their southern counterparts. Despite what Edgar says in the quote above, Figure 30 shows that the shafts would clear the blocks immediately lining the west of the Grand Gallery even if they didn’t deviate at all. However one correspondent, Keith Hamilton, seems to have come up with a variation on this theme.[36] He maintains that not only the blocks lining the Grand Gallery, but also those behind them for some way, needed to be carefully positioned and accurately worked to ensure the structural integrity of this part of the edifice – citing as an example the accurately dressed stones that continue for some depth behind the Niche in the Queen’s Chamber before giving way to more roughly dressed core blocks. Given what we now know about how the shafts are constructed – as a ‘U-shape’ carved out of then-upturned upper blocks that rest on separate, flat flooring blocks – this wouldn’t have gelled well with the requirement for buttressing.

This explanation certainly correlates with the fact that the northern King’s Chamber shaft deviates west early on (see Figure 30), which based on the above it would need to do even though from a side-on perspective it only runs behind the very top and relatively narrow part of the Grand Gallery (see Figure 2). Meanwhile its Queen’s Chamber counterpart only deviates after some distance – perhaps at that point when it would otherwise start to run through the support blocks behind the middle of the Gallery.

OPENING GANTENBRINK’S DOOR

Original plans to ‘open Gantenbrink’s door’ at the end of the southern Queen’s Chamber shaft during the millennial celebrations at the Plateau were shifted to the year 2000 long before the event itself. But even this never came to fruition, and by early 2001 Hawass was responding to questions with a seeming lack of interest:[37] ‘We hope soon that some people will come… I am not in a hurry.’

THE PYRAMID ROVER PROJECT

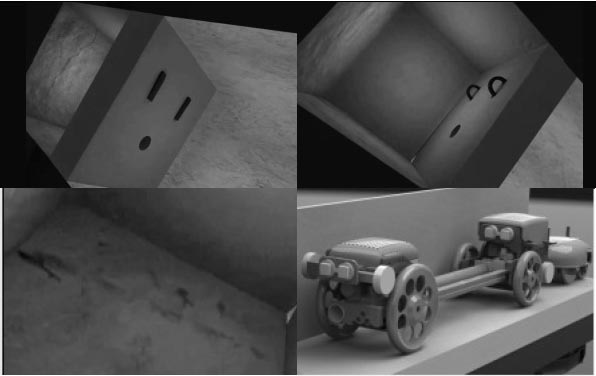

Nevertheless in 2002 a new team, sponsored by the National Geographic Society and co-ordinated by the SCA and the Giza Plateau Mapping Project at Chicago University, made some significant discoveries.[38] Using a robot designed by US company iRobot and costing $250,000 they first investigated the southern Queen’s Chamber shaft. The Rover picked up the two copper ‘handles’ on the ‘door’ (see top left picture in Figure 42) and, having scanned it and found it to be only around 2.5 inches thick, they drilled a hole just large enough to insert a small, fibre-optic camera (the hole can be seen just below centre in both top pictures in Figure 42). It then picked up another blocking slab or door around 7.5 inches further on but, with a fixed camera and poor lighting, nothing more could be gleaned from the resulting photo. Meanwhile in the northern shaft they found that after the first kink it travelled for approximately 26 feet in a north-westerly direction before bending back towards due north. Its total length was found to be similar with, most important, another 'door' with copper handles at the end.

So what would happen next? Who could come up with the advanced robotic technology required to investigate further?

TOMB TREKKER

In 2004 Hawass entered discussions with a team from Singapore University, and by the end of the following year their ‘Tomb Trekker’ was ready for inspection.[39] Sadly though it seems he wasn’t satisfied and invited in competition.

Figure 42: Computer Simulations of Copper Handles and Masons Marks [40]

THE DJEDI PROJECT

Dr TC Ng, a Hong Kong dentist who had previously specialised in making precision tools for space exploration, was intent on designing a robot that could explore the shafts.[41] After initial rejection by Hawass, then an aborted attempt to work with the Singapore team, he teamed up with a former colleague from the Mars Lander project, British inventor Shaun Whitehead. They enlisted the help of a team from Manchester University who then migrated to its nearby Leeds equivalent, while financial assistance and 3D modelling construction expertise was provided by the same Dassault Systems we’ve encountered several times already. The project was named after the Egyptian magician consulted by Khufu when planning his edifice, as reported in chapter 5, and they won over Hawass.

This was at least partly because Djedi was designed to be as non-intrusive as possible, meaning it departed from the upper and lower caterpillar tracks of its predecessors and used a car-like design of four open wheels instead (see bottom right picture in Figure 42). It worked somewhat like an ‘inchworm’, exerting a light outward force via adjustable soft pads near the rear axle to keep the robot braced against the sides of the shaft, then extending the front axle forward, then bracing that with similar pads and pulling the rear axle up the shaft – and so on, in turn. It was also fitted with a miniature ‘micro-snake’ camera that was flexible enough to have a full 360 degrees of motion, accompanied by six strong miniature LED lights.

Making their first visit to the Plateau in 2009 the team investigated the ‘door’ at the end of the southern shaft first, and close inspection of the missing triangular section in the bottom right-hand corner revealed that it’s a slab held in place via shallow recesses in the left and right-hand walls of the ‘inverted U’ block, while the ceiling and floor block contain no equivalent recesses. All surfaces in the miniature chamber behind are again of polished Turah limestone, except for the face of the blocking stone at the far end, which is rough and undressed. Meanwhile the rears of the copper handles were revealed to be formed into loops (see top right picture in Figure 42). In addition the camera picked up a red-ochre mason’s line on the floor of the chamber running more-or-less parallel to the right-hand wall, with between them three red glyphs – which are almost certainly mason’s marks written in hieratic shorthand, possibly representing the numbers 1, 20 and 100 or 200 respectively (see bottom left picture in Figure 42). Unfortunately the revolution in Egypt early in 2011 hampered the team’s attempts to return and investigate both the far wall of this chamber and the ‘door’ in the northern shaft to see if it fronted something similar. Indeed Whitehead gave me this rather depressing update in 2020:[42]

We were told to reapply for the mission in the same away as every other Egyptological mission was supposed to after 2010. Of course we did that, and actually expanded our scope to do other survey work in the pyramid. We kept asking about the status of the application, and either received no response, or were told that ‘the time is not right’. The next thing we heard was that the ScanPyramids team were working in the pyramid. Frankly, I gave up, because we all have other equally exciting and important projects to fill our time, and it was clear that we were getting nowhere.

What a terrible failure to capitalise on the chance to further investigate one of the few major enigmas of the Pyramid, especially after such a huge amount of effort went into putting together a brilliant piece of equipment. Having said that, even Djedi’s one visit did answer a great many questions about the ends of the Queen’s Chamber shafts.

AN ANCIENT INTERCOM?

The indefatigable Houdin has again provided some fascinating input into the debate concerning the Queen’s Chamber shafts in particular.[43] To understand this, he proposes that the major new challenge the builders of the Great Pyramid deliberately set themselves – to prove their increasing levels of skill compared to their predecessors – was to build a chamber high up in the infrastructure that wouldn’t be ready until years into the build. Of course what they didn’t know was whether Khufu would last that long. So they gave themselves two insurance policies for if he died beforehand, in the form of the Subterranean Chamber and the Queen’s Chamber – and remember from Edrisi’s account in chapter 1 that the latter originally had a coffer built into it just like the King’s Chamber. According to Houdin all this, including access passages and so on, had to be designed from the outset. This is a variation on the replanning argument we encountered in various places in the main chapters, but it represents replanning in advance – if that makes sense.

As far as the Queen’s Chamber shafts are concerned, he follows JP Lepre’s lead in pointing out that they finish at exactly the same horizontal level as the roof of the uppermost Relieving Chamber (although as we saw in chapter 7 it’s unclear how Lepre arrived at this conclusion). Houdin therefore contends that they may well have acted as prototypes for the King’s Chamber shafts. These, he maintains, did indeed have the primary purpose of providing essential ventilation during the burial – bearing in mind that this chamber, being so much higher than the Descending and Ascending Passages used to access it, receives hardly any fresh air or cooling otherwise. But, as I pointed out in chapter 8, wouldn’t easier-to-build horizontal shafts have achieved the same purpose? In answer to this, Houdin maintains they also had a secondary or dual purpose – something talented and inventive architects like the Ancient Egyptians love to build into their designs. What was this? To act as a low-technology intercom system linking the north and south sides of the Pyramid, especially while the Grand Gallery was being used as part of a counterweight system for the largest and heaviest granite blocks. This would require them to ascend into the structure so they could operate for longer.

In support of this ingenious claim he adds four lines of argument. First, that the walls of the Queen’s Chamber were smoothed to assist with acoustics. Second, that the ‘doors’ at the end of each shaft were in fact just blanking plates, slotted into position at each level as the structure rose to prevent rubble and other detritus from clogging up the intercom when it wasn’t in use – meaning the copper ‘handles’ would have been exactly that, except with rope and so on attached through the hoops at the rear. The ‘chambers’ behind these doors would then be nothing of the sort, but merely represent the gap between the final position of the blanking plates and the next unworked core block placed in the layer above. Third, the blocks in the Queen’s Chamber that eventually blanked these shafts off were left sticking out ‘like drawers’ until they had served their purpose, and were then pushed back properly into their recesses.

My only questions would be as follows. First, why were the shafts finished using smooth Turah limestone for quite some distance at their upper extremities, yet left quite rough elsewhere? Second, why do the rough-hewn blocks in the far walls of the ‘chambers’ lie parallel to the ‘doors’ instead of just being horizontal? Third, surely the blanking plates would have been a little too wide for the rest of the shaft, given that they slot into grooves in the walls in their final positions? Fourth, I can’t see how the shafts would have been open in the Queen’s Chamber even with the blanking blocks sticking out. But this may just reflect my own ignorance of the details of what is undoubtedly an ingenious theory, and arguably the most logical presented to date – which may well prove right in time.

THE ORION CORRELATION

Another area in which I’ve engaged in extensive debate is the Orion correlation theory originally covered in chapter 9.[44] My website contains constructive discussions with a number of key researchers, including Egyptologist Kate Spence, astronomers Ed Krupp and Tony Fairall, and John Legon.[45] Nevertheless the main thrust is my interchange with Bauval himself.

The first involves criticisms that he’s made concerning my original comments on the 10,500 BCE dating. Because it was the software he used when he wrote The Orion Mystery, I too used SkyGlobe to derive the angles of the belt stars in the different epochs that I presented in Figure 35 (in fact I’ve updated these figures slightly having re-checked my measurements). However, he points out that this software fails to take into account such complex astronomical factors as proper motion, nutation, aberration and refraction, merely accounting for precession. To establish these figures properly he asked Professor Mary Bruck, a former lecturer in astronomy at Edinburgh University, to calculate them. Her results indicate that the angle formed by the line running through Al Nitak and Al Nilam at culmination in 10,500 BCE was between 40 and 43 degrees from the horizontal, the variation being dependent on whether or not nutation was allowed for in the calculations. Bauval’s assertion that this is pretty close to the required 45-degree angle is a fair one.

Yet one is entitled to ask how he thought the angle was 45 degrees using SkyGlobe when he originally presented his theory? His answer is that the ‘lock’ on the 10,500 BCE date was always much less the precise angle of the belt stars and much more down to two other factors. First, that at this date the constellation of Orion was at its lowest point in the precessional cycle (which I don’t dispute). Second, that at the exact point of the sunrise on the vernal equinox in that epoch, not only did the constellation of Leo provide the backdrop in the east, but Orion was also exactly at its point of culmination in the southern sky. (The emphasis on these latter points is somewhat underplayed in Bauval’s previous work, which is where the confusion arose for me, and I’m sure for a great many other people.[46]) However, even if this latter assertion is true – I’ve not had the time to obtain the appropriate software to check it – it’s clearly an astronomical ‘coincidence’. Although I accept that the Ancients read much into such events, this one is undoubtedly rendered less symbolic if the Sphinx was not even there at this time – which, as we’ve seen, I don’t believe it was.

Of course it’s also worth mentioning that, if Houdin is right about the air shafts, they have nothing to do with symbolism and everything to do with function. Given that no other pyramid has anything similar, he questions why none of Khufu’s counterparts before or afterwards needed such shafts for their symbolic afterlife journeys to the stars? Is the answer simply that his was the only pyramid with a high-level chamber requiring ventilation?

In any case, though, there are far more fundamental issues at stake with Bauval’s theory than just the supposed date correlation. The other significant area of discussion on my website has been my two main criticisms that I believe completely undermine the basic Orion Correlation theory. These are included in chapter 9, but let’s remind ourselves. First, there’s a massive differential between the size of the Third Pyramid and that of Mintaka relative to their earthly and celestial counterparts. One might just about argue that with symbolism such accuracy isn’t important. However my second objection is surely far more significant, and it’s the evidence for major replanning of the Second and Third Pyramids – in terms of size and possibly also location.[47] Both of these detract from the fundamental hypothesis of a plan for the layout of the Plateau to such an extent that, arguably, the dating issues become irrelevant.

OTHER MASTER PLANS

Generally speaking my replanning arguments extend to any attempt to establish a ‘master plan’ for the Plateau. However, because I believe that people should be allowed to make up their own minds, on my website I reproduce or link to a number of alternatives based on geometric interpretations.[48] Having said that, in his paper A Cautionary Tale correspondent Barry McCann makes the fascinating observation that, from his own experience of designing a new house from simple geometric principles, such a plan has an ability to take on a life of its own – and that many relationships appeared in his designs that were never an intentional part thereof.

A FINAL WORD

[This has been left unchanged from the original editions.] Although we’ve been somewhat scathing about a number of people in this book, because we believe they merit some degree of criticism, it should be clear that we’ve only done this when we question their motives. Those with whom we disagree purely on an intellectual level we hope have received somewhat kinder treatment. Nor have we allowed our views to be biased by personal acquaintance, for there are some who have been criticised even though, for example, they may have helped us with our research. It gave us no pleasure to do this, and we realise that we leave ourselves open, in a few cases, to accusations of being disingenuous, but in our view this is the price one must pay for being entirely honest and open-handed in one’s treatment of the facts.

Above all, it’s in no sense our right to act as judge and jury on people’s actions. Instead you, the readers, will make up your own minds about the ins and outs, whys and wherefores, and rights and wrongs of the tangled web of politics and intrigue which we’ve laid before you in this book. So should, indeed must, it be.

Since the book was originally published, we’ve been accused repeatedly of uncritically accepting the orthodox standpoint. In fact, the truth is that, like so many others, we were in danger of uncritically accepting the alternative standpoint before we conducted the detailed research on which this work is based. We hope that we’ve redressed the balance somewhat so that readers have the chance to consider both sides of the arguments, and make up their own minds accordingly. Although we feel we’ve been able to rationalise many of the ‘enigmas’ of the Plateau within an orthodox context, in no sense do we feel that all of the magic and excitement of Giza and its incredible monuments is removed as a result. Almost certainly the Ancient Egyptians did have an advanced understanding of acoustics which was coupled with an esoteric world view of breathtaking wisdom and complexity. As long as we devote our attention to those issues that remain genuinely unexplained, there’s plenty of truth still waiting to be discovered…

[1] See ‘Additional Papers/Discussions’ at www.ianlawton.com/gttindex.html.

[2] El Daly actually conducted seven years of research using uncatalogued manuscripts in private and public collections. He also reports that there were quite a few monuments and artifacts in Egypt that, like the Rosetta Stone, had several scripts inscribed on them – for example the famous statue of King Darius the Great (5th century BCE), which has hieroglyphic text as well as three other languages, and now resides in the Tehran Museum.

[3] Taken from his review of Bauval’s The Cosmic Womb at www.jasoncolavito.com/book-reviews.html.

[4] See the comments section after his review at www.jasoncolavito.com/blog/review-of-scott-creightons-the-great-pyramid-hoax-part-two.

[5] See www.ianlawton.com/gpp.html.

[6] See www.ianlawton.com/pc1.html.

[7] See www.ianlawton.com/pc.html.

[8] See www.catchpenny.org/mmbuild.html.

[9] Reproduced by kind permission of Mike Molyneaux.

[10] This was originally on his website at www.construire-la-grande-pyramide.fr, now defunct, but this work has been incorporated into his later book.

[11] See Brier, ‘Return to the Great Pyramid’, Archaeology 62:4 (2009) reproduced at https://archive.archaeology.org/0907/etc/khufu_pyramid.html.

[12] See www.youtube.com/watch?v=3NCK99mQUxw.

[13] See www.ianlawton.com/pc.html.

[14] See www.geopolymer.org/faq/faq-for-artificial-stone-supporters.

[15] See www.geopolymer.org/archaeology/tiahuanaco-monuments-tiwanaku-pumapunku-bolivia.

[16] See www.ianlawton.com/am.html.

[17] Dunn's full report of his visit to the Petrie Museum in November 1999 can be found on his website at www.gizapower.com.

[18] See www.hallofmaat.com/papers.html.

[19] Clarke and Englebach, Ancient Egyptian Construction and Architecture, chapter 18, p. 203. The original is a scene in the 5th Dynasty tomb of Sahure at Abusir, now in the Cairo Museum.

[20] See Elkington, David, Ellson, Paul and Reid, John, In the Name of the Gods, chapter 12, pp. 394–8 and also the plates section.

[21] See the first edition of The Great Pyramid Passages and Chambers, Volume 1, Part 2, letter 19, pp. 333–5.

[22] See Foster, Mark, Trial Passages: A Message in Stone? at www.artifice-design.co.uk/rosetau/trial.html. This is reproduced in Ralph Ellis’ Thoth.

[23] See Ellis, Ralph and Foster, Mark, Tunnel Vision at www.artifice-design.co.uk/rosetau/tunnel_vision.html.

[24] See www.cheops.org.

[25] Reproduced with the kind permission of the HIP Institute.

[26] See Marchant, Jo, ‘Cosmic-ray particles reveal secret chamber in Egypt's Great Pyramid’, Nature (2nd November 2017) at www.nature.com/news/cosmic-ray-particles-reveal-secret-chamber-in-egypt-s-great-pyramid-1.22939.

[27] See ibid.. As far as the internal ramp element of their theory is concerned, however, at the same time and with no real explanation Brier is reported as saying: ‘These data suggest that the ramp is not there. I think we’ve lost.’

[28] See Jarus, Owen, ‘What's Hiding Inside Egypt's Great Pyramid?’, LiveScience (16th January 2018) at www.livescience.com/61435-great-pyramid-mysterious-voids.html

[29] See Fukushima, Shingo, ‘Team to re-scan Great Pyramid of Giza to Pinpoint Hidden Chamber’, The Asahi Shimbun (11th January 2020) at www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/AJ202001110001.html.

[30] See www.ianlawton.com/as.html.

[31] Much of what follows is a summary of a paper he prepared in 2019 entitled Climate Change and the Age of the Great Sphinx, published at www.academia.edu.

[32] See Origins of the Sphinx, chapter 2.

[33] From an interview on the Joe Rogan Experience radio show, 31st May 2018, at www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vka2ZgzZTvo.

[34] This comes from the first edition of The Great Pyramid Passages and Chambers, Volume 1, Part 2, letter 10, pp. 218–9.

[35] This comes from a ‘discourse’ given by Morton in 1929, and included by the publishers as part of their Foreword to an updated edition containing all three volumes.

[36] For his full email see www.ianlawton.com/ss.html.

[37] See Hawass' website at http://guardians.net/spotlite/spotlite-hawass-2001.htm.

[38] This information comes from an excellent and in-depth article by Keith Payne at http://emhotep.net/the-djedi-project-the-next-generation-in-robotic-archaeology. See also the 2002 documentary made by National Geographic entitled 'Into the Great Pyramid'.

[39] See ibid..

[40] Reproduced with the kind permission of the Djedi Project/Shaun Whitehead.

[41] What follows comes again from Keith Payne’s article. For the full report see ‘The Djedi Robot Exploration of the Southern Shaft of the Queen’s Chamber in the Great Pyramid of Giza, Egypt’, Journal of Field Robotics 30:3 (2013), pp. 323-48.

[42] In an email dated 29th January 2020.

[43] See Houdin’s contribution dated 15th January 2012 in the comments section at the end of another excellent and in-depth article by Keith Payne at http://emhotep.net/the-pyramid-shafts-from-dixon-to-pyramid-rover.

[44] See www.ianlawton.com/oc.html.

[45] Two papers of particular importance to this debate can be accessed here. The first is a rarely-discussed one by Egyptologist Jaromir Malek that first appeared in Discussions in Egyptology 30 (1994). The second is Kate Spence's 'Egyptian Chronology and the Astronomical Orientation of Pyramids', Nature 408 (2000), in which her theory casts some doubt on the Ancient Egyptians' knowledge of precession.

[46] Although the explanation provided in his more recent book, Secret Chamber, Appendix 2, pp. 374–7 is far more lucid.

[47] I have fleshed out the replanning argument in particular in a paper published at www.ianlawton.com/oc8.html entitled The Fundamental Flaws in the Orion-Giza Correlation Theory.

[48] See www.ianlawton.com/pg.html. These include contributions from Wilfred Nieman, Keith Squires, David Ritchie and Simon Cox, Mick Saunders and Terry Maxwell.