PREFACE

© Ian Lawton 2020

In the Western world we’re pretty familiar with the book of Genesis from the Old Testament. How God created the world in six days, and rested on the seventh. How he created the first man, Adam, and then his companion Eve. How Adam’s descendants acted as patriarchs overseeing human affairs up to the time of the great flood, which God sent to destroy humankind. How Noah was spared in the ark and went on to father the new human race.

Over the last few centuries, spurred on by Darwin and the breakthroughs of scientists in all fields who‘ve followed in his footsteps, we’ve increasingly been told to reject all of this as nothing more than a fable constructed to foster a religious outlook in simple people – and it’s probably not unreasonable that any traditionalist who still insists the world was created in 4004 BCE receives pretty short shrift.

Yet many post-flood biblical traditions originally dismissed as mere stories were validated in the late nineteenth century when Mesopotamian cities mentioned in the Old Testament – for example Nineveh, Erech and Ur – were unearthed by intrepid explorers such as Sir Austen Henry Layard and Sir Leonard Woolley.[1] Similarly the discovery of Troy by Heinrich Schliemann, and of the Minoan civilisation in Knossos on Crete by Sir Arthur Evans, proved that settlements had existed at both sites since around 3000 BCE, forcing a similar revision of orthodox thinking about certain Greek traditions. These wonderful breakthroughs came from the dedication and bloody-mindedness of pioneers who refused to accept the conventional wisdom. In that time it has also become clear that reports of a catastrophic flood exist not just in the Bible but also in sacred texts from all around the world.[2] Meanwhile various researchers have attempted to show that these are backed up by geological evidence, to such an extent that in recent decades the idea has received widespread publicity and a fair degree of acceptance.

As a result of all this in the mid-1990s, in my formative years as a writer and researcher, I became fascinated by the possibility that the sparse and enigmatic record of a widespread pre-flood culture in the early chapters of Genesis might also contain some element of truth. So I set myself the challenge of unearthing as many of the ancient texts and indigenous traditions from around the world as I could, to find out what the rest of our ancestors might have to say about any early race of people on our planet who were wiped out by some sort of major catastrophe.

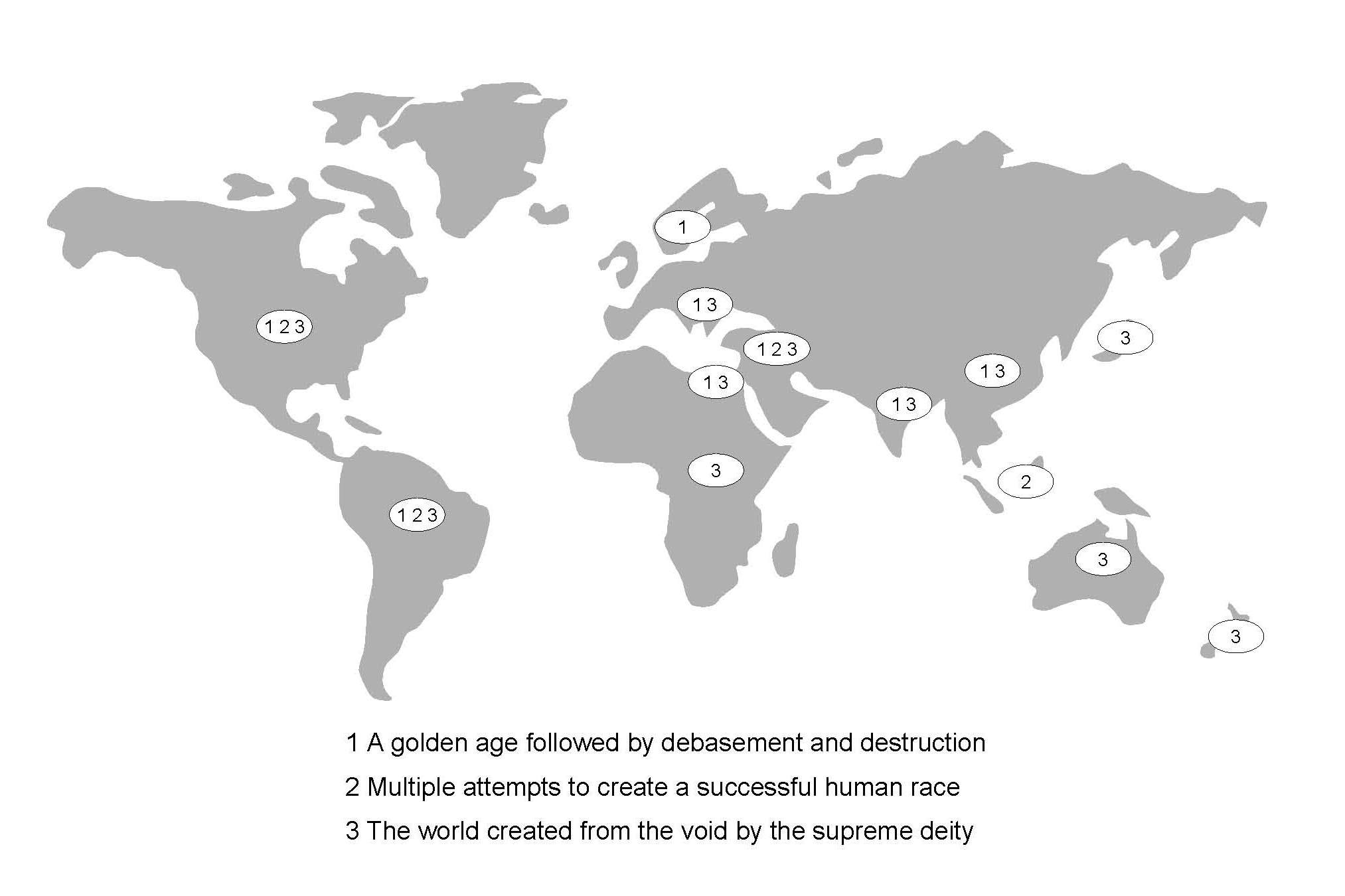

Figure 1: The Common Themes in Ancient Texts Around the World

Most of my original research was undertaken in the days before the internet made it so incredibly easy, and I was often spending weeks at a time in the British Library poring over obscure anthropological studies and other rare manuscripts. But I became increasingly enthralled as I discovered that various ancient cultures right across the globe preserve a tradition of a forgotten race that was originally highly spiritual but degenerated until it was wiped out. As can be seen from Figure 1 these traditions are far more widespread than is sometimes recognised. Were all these too just simple fables put together by relatively primitive, superstitious cultures, or did they contain some grain of truth? Intuitively I felt the latter might just be true.

Having said that, in any study of this kind we must proceed with extreme caution. Nowhere was this brought home to me more than by the issue of the so-called ‘King Lists’ from Ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt and China, which acted as the forerunners for the biblical list of pre-flood patriarchs.[3] Originally I was excited by these as potential proof of a pre-catastrophe civilisation – until, that is, I was confronted by the cold, hard scholarship of Garrett Fagan, professor of ancient history at Penn State University:[4]

In every instance, to my knowledge, the lists start out with the gods. The lists then function to show (a) the antiquity of the regime or culture that composed them and (b) that regime or culture’s direct connection with the gods. It is much harder to challenge a divinely ordained system than an admittedly human one.

It seems obvious once pointed out that many of the messages found in the ancient texts and traditions are explainable in sociological terms, especially when acting to reinforce the rule of the prevailing politico-religious hierarchy. Allied to this it’s clear that many of the versions of sacred texts that have survived have been repeatedly edited over time by different sets of cultural leaders with just such motives, making it much harder to see through the fog and establish the nature of the original underlying message.

Then, of course, there’s the whole issue of symbolism in what is commonly termed ‘mythology’. In the first of his four-volume masterwork The Masks of God, published between 1959 and 1968, that most respected of experts in this field, Joseph Campbell, describes how any would-be interpreter is walking something of a tight-rope:[5]

It must be conceded, as a basic principle of our natural history of the gods and heroes, that whenever a myth has been taken literally its sense has been perverted; but also, reciprocally, that whenever it has been dismissed as a mere priestly fraud or sign of inferior intelligence, truth has slipped out the other door.

To some degree Campbell developed the work of his equally eminent predecessor Carl Gustav Jung, who prefaced the English version of his Psychology and Alchemy, first published in 1953, with the following overview:[6]

Some thirty-five years ago I noticed to my amazement that European and American men and women coming to me for psychological advice were producing in their dreams and fantasies symbols similar to, and often identical with, the symbols found in the mystery religions of antiquity, in mythology, folklore, fairytales, and the apparently meaningless formulations of such esoteric cults as alchemy… From long and careful comparison and analysis of these products of the unconscious I was led to postulate a ‘collective unconscious’, a source of energy and insight in the depth of the human psyche which has operated in and through man from the earliest periods of which we have records.

There can be little doubt that Jung’s symbols, or archetypes, are the key to unlocking the hidden meaning of much of the body of myth from around the world that our ancestors have left as their legacy. This is one of the main reasons why the most sacred texts and traditions of all ancient cultures can appear so enigmatic and obscure to the uninitiated – because to a large extent the archetypes, whether in picture or textual form, are not designed to speak to the logical left brain, but rather to the intuitive right brain that’s the link to both the personal and the collective unconscious. Nowhere is this more clearly demonstrated than in the texts of the Ancient Egyptians, whose hieroglyphic symbols often had multiple and subtly different meanings appreciated only by those fully initiated into their mystery.

It is also the case that the earliest texts and traditions of our ancient cultures tended to be handed down orally, even after they’d also been recorded in writing. Indeed we often find important philosophical concepts embedded within a story format, not only so they could be more easily memorised and would be entertaining to relate, but also so that they might better penetrate the non-logical, subconscious mind. This allowed them to survive over centuries or millennia, even if the real understanding of their symbolic message was lost on most of the audience. In addition, of course, couching such traditions in symbolism and archetype was particularly useful when, as has happened throughout history, esoteric sects were trying to maintain them under threat from a dominant religious orthodoxy.

The foregoing analysis is fine as a general summary of the modern approach to mythology. But are there any grey areas, even concerning the time before the flood, where it would be right to debate whether something more than just symbolism and myth underlies the relevant texts and traditions? Might they have some basis in fact that, albeit perhaps in only the broadest of senses, can act as a pointer to real historical events? My research led me to believe these grey areas did exist, particularly in the passages I repeatedly encountered that appeared to describe a veiled history of humankind only hinted at in Genesis.

Not only that, but several other themes were continually cropping up too, in particular those dealing with the ‘creation of humankind’ and the ‘origins of the world’. Again their spread is shown in Figure 1. In my view many orthodox scholars tend to oversimplify these aspects of the traditions of our most celebrated historical civilisations by concentrating on the anthropomorphic qualities of the various well-known gods that take centre stage. By contrast I became increasingly convinced that, when properly interpreted using the nascent spiritual and esoteric worldview I was starting to develop, these consistent themes revealed their originators to be anything but intellectual dwarfs trying to concoct a simplistic philosophical framework with which to make sense of the world around them. It seemed to me they had a highly sophisticated worldview, and probably a common source of spiritual wisdom on which to draw.

We are now some two decades on, but the reason I’m rewriting and republishing this work is that I continue to believe that a proper appreciation of the legacy left by our forebears across the globe, and a reappraisal of the consistent elements of their worldview from a spiritual perspective, is long overdue. This just may take us closer to uncovering the underlying messages in their texts and traditions than we’ve ever been before – and may also lead us, at last, to a true understanding of the legend of the lost civilisation of ‘Atlantis’ that has so beguiled us ever since Plato first mentioned it.

Nevertheless this work couldn’t stand up to scrutiny if it relied solely on the reinterpretation of ancient texts and traditions. In support, first we can turn to archaeology, where a mounting body of orthodox artifactual evidence increasingly suggests that modern humans have been around in highly cultured form for rather longer than has hitherto been accepted. Second we can bring in the geological evidence that in the relatively recent past our planet has been rocked by at least one major catastrophe, which could easily have wiped out all traces of any advanced culture that prospered beforehand. Some of the older material in this area has proved to be of little value, but important new research keeps catastrophe theory very much alive and kicking.

The number of alternative researchers who have put forward unconventional views of the history of our planet, and of human life thereon, has proliferated dramatically in the last half century. Indeed, as we’ll see later, several of these are the very authors who inspired me to begin my own quest. But it wasn’t long before I found out that unfortunately many of them can be somewhat lacking in scholarship. Even when I was conducting the original research for this book my experience with my first book Giza: The Truth – first published in 1999 but now the first volume in this newly-published ‘Prehistoric Truth’ series – had already taught me not to take anything written by alternative authors on trust. Instead one must always go to the primary source to check out their references and interpretations. In doing so I also learned that some of them aren’t averse to deliberate misinterpretation and even falsification of supposed evidence.

A case in point was when I became hugely excited by New-York journalist Zecharia Sitchin’s apparent revelations about the Mesopotamian texts that predate the Old Testament and, it turned out, provided the antecedents for biblical themes such as the story of the flood and its hero. Not only did he claim to be one of the few scholars in the world able to interpret their complex cuneiform scripts but, far more exciting, he announced that that they described how humankind had been genetically created by a race of extraterrestrials called the ‘Anunnaki’ from a planet called ‘Nibiru’. These revelations initially came in 1976 with his first book, The Twelfth Planet, but over the next few decades they were augmented by a number of follow-ups in his ‘Earth Chronicles’ series. By the time I was introduced to his work by a girlfriend in the mid-1990s, like so many other people I’d already developed the inner sense that not everything about our orthodox, materialistic view of life on Earth was to be trusted – and that there must be something more. To a complete novice like me, Sitchin’s revelations were like manna from heaven, the answer to all my doubts, the key to the alternative history that so many of us suspected must exist. The problem came when I decided to do something that most casual readers don’t have the time or energy to do. I checked out the Mesopotamian texts for myself.

It didn’t take long to obtain translations by orthodox scholars, and to realise that something was very, very wrong. Not only did Sitchin not have any proper endnote references in his books – something that should perhaps have been a dead giveaway even to a novice researcher like me – but also the references within the text were often sporadic and incomplete. This meant that tracking down passages in texts he claimed to quote from proved close to impossible in some cases. Undaunted, I began to list all of the older Sumerian and later Akkadian texts I could locate in the translations made by orthodox scholars, and to summarise their contents. I then made a case study of Sitchin’s claims concerning the word shem, which he insists really means ‘sky rocket’ even though experts are agreed that it’s mainly used to denote ‘name’ or ‘reputation’. It was then, when I also consulted those few scholars who had been prepared to devote precious time to commenting on Sitchin’s work, that the true extent of his falsification was revealed. For a start he was very far from the sort of linguistic expert he claimed, instead randomly mixing up Akkadian and Sumerian script to suit his wild interpretations and showing almost total grammatical ignorance into the bargain. Worse still he would sometimes leave out interim lines or phrases in his extracts, with no ellipses to show that he’d done so, which when reinstated from orthodox translations rendered his interpretations completely untenable. This could only imply one thing: the deliberate and conscious falsification of evidence on his part.

At the end of this somewhat painful process I collated my research into a number of papers published on my website, which have now become the third volume in the ‘Prehistoric Truth’ series, Mesopotamia: The Truth.[7] But the reason I include all this here is because it’s highly instructive. We have to adopt the highest levels of discernment when reading, writing and researching alternative history, and if we don’t we might as well be indulging in complete fantasy. Entertaining fantasy, perhaps, but fantasy nonetheless.

I hope it’s fair to say, without sounding too arrogant, that Giza: The Truth gave me certain credentials as an independent and discerning author who isn’t afraid to admit when orthodox scholars have got it right – which remains, in my experience, the majority of the time. They are by no means infallible, any more than any of the rest of us, and of course we can all be selective in what we research and present, even if only as a result of entirely subconscious bias. But by and large they haven’t achieved what they have by being narrow-minded imbeciles. Of course some leading alternative researchers are masters of rabble-rousing, and their followers love to hear them pouring vitriol on anything to do with the orthodoxy. But For many years I’ve felt that it’s time for a new, more scholarly approach to alternative history to come to the fore. An approach that has the independence and freedom to question aspects of the orthodoxy that possibly deserve re-evaluation, but without blatant disrespect. An approach, too, that doesn’t gloss over or remain ignorant of orthodox arguments, but instead faces them head on.

One key aspect of all this is that I and my co-author on Giza: The Truth, Chris Ogilvie-Herald, felt that up to that point there’d been an almost complete lack of peer review and constructive criticism among the ‘club’ of leading alternative authors. So after it’s first edition came out I began to take issue with them – not because I liked the sound of my own voice or had a point to prove, but in the genuine hope that highlighting those theories that were clearly nonsensical or lacked coherence would actually advance, at least in some small way, the alternative movement’s general cause and credibility. I carried on in the same vein in this second book when it was first published as Genesis Unveiled in 2003. Of course I understand that there are commercial considerations for modern authors under pressure from hard-pressed publishers, but surely the constant underlying aim should be to move together towards a better understanding of the enigmas of our past, and to share this research in an honest and responsible way with the general public. What is more there are a hard core of real enigmas that remain largely untouched by orthodox scholars but do deserve serious study, without us needing to fabricate all sorts of weird and wonderful nonsense.

In particular when postulating a ‘forgotten’, ‘lost’ or ‘hidden’ former race of people on Earth, some alternative researchers have demonstrated a disturbing lack of understanding of orthodox arguments in three main areas. The first is human evolution, where certain of them provide supposed evidence of extreme antiquity for modern Homo sapiens. Not only is this evidence fatally flawed anyway, but they also fail to place it in any philosophically or scientifically logical context. Meanwhile others propose that extraterrestrial intervention is the only answer to supposed evolutionary enigmas they appear not to have fully investigated. The second is the role not just of symbolism but also of context in myth. So some of them, for example, produce entirely literal translations of specific texts with no regard for the context of similar themes in other cultures. The third is the dating of monuments from our earliest historical civilisations, where again the significant body of contextual evidence archaeologists have painstakingly amassed is often disregarded. Nowhere is this latter phenomenon better demonstrated than in attempts to ascribe a far earlier date to the Great Pyramid and Sphinx, a subject covered in detail Giza: The Truth that we’ll also touch on in Part 2.

Other alternative researchers take a different tack and, even if they accept the orthodox view of human evolution and of the dating of ancient monuments, suggest the level of technology displayed by these early civilisations couldn’t possibly have ‘developed overnight’ – some even arguing that highly advanced technology must have been handed down by survivors from Atlantis or introduced by extraterrestrial visitors. Yet they fail to properly appreciate just how much can be achieved by a civilisation like that of the Ancient Egyptians with superb organisation and focus, but not necessarily high levels of technology in the modern sense of the word. When we understand that there’s a development period in the archaeological record of these civilisations that such researchers tend to ignore, and we remind ourselves of how rapidly our modern Western world has developed in only a handful of centuries, these arguments just don’t stand up.

By contrast, rather than using the argument that the supposedly advanced technology of our earliest historical civilisations implies that previous counterparts must have existed, I’d argue there’s prima facie textual as well as indirect archaeological evidence of an extensive pre-catastrophe civilisation – although to me there’s nothing even remotely conclusive to suggest they were technologically advanced. They might have constructed settlements of considerable size, but not necessarily with huge structures, advanced techniques or even durable materials. If located in the right areas of the globe, and not competing for scarce resources, they might have developed a high state of culture – but one based primarily on inter-group cooperation and trade, knowledge development and education. We always tend to assume others must be like ourselves, and we’re only too aware of how aggressive and war-mongering we can be, even in the modern world. But what if originally they were nothing like us? What if they lived lives of peaceful cooperation and harmony, both with nature and each other, for many millennia – until, like us, they became slaves to the great god of material progress.

Above all, instead of extrapolating the supposed technical knowledge of our post-catastrophe ancestors back to their pre-catastrophe forebears, we should arguably concentrate on tracing the roots of their spiritual knowledge. Although other commentators have explored the symbolism and esoteric wisdom displayed by our earliest historical civilisations, they often seem to fall short of being able to put this into any meaningful metaphysical context. So we will re-examine what really underlies the consistent motifs found in the creation of humankind and origins of the world traditions from around the globe, and consider the possibility that they might display a profound spiritual wisdom. We will then use this as the key to unlock their hidden messages regarding our forgotten, pre-catastrophe race. It is their original spiritual advancement in a ‘golden age’, their subsequent debasement through concentration on the material world and forgetting of their spiritual roots, and their consequent destruction, that appears to shine through loud and clear. Is this just another socio-political, religious or psychological construct – or does it carry an echo of real events?

All in all, then, when I do depart from orthodox opinion and postulate that a culturally advanced but non-technological civilisation may indeed have emerged on our planet tens of thousands of years ago, I do so with some hope that it will be seen to be more than just wild speculation and fantasy.

[1] For more information on this see Volume 3 of the ‘Prehistoric Truth’ series, Mesopotamia: The Truth, chapter 1, pp. 12–18.

[2] A multitude of ancient texts and traditions from nearly every continent on the globe record such an event. We won’t examine the detail of all of these in the current work because they’ve been well chronicled by others, but we will meet with many of them in due course. For comprehensive descriptions and discussion see, for example, Oppenheimer, Eden in the East, chapters 8–10. In addition a number of websites document flood myths; see, for example, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flood_myth.

[3] Nevertheless I have published the detailed contents of all these king lists, taken from the original sources, on my website, not least because this information is rarely properly recorded. See my paper Problems with King Lists at www.ianlawton.com/att1.html.

[4] Personal correspondence, 23 February 2001.

[5] Campbell, Primitive Mythology, Introduction, p. 27.

[6] Jung, Psychology and Alchemy, prefatory note to the English edition, p. v.

[7] The detailed support for these strong allegations is provided in Part 2 thereof. It is worth pointing out that Sitchin never deigned to respond to any of his linguistic critics in any detail at all.